In the era of Mandarin, where will dialects go?

Translated from 普通话的时代,方言何去何从?

In today’s world, diversity in every aspect is being gradually destroyed. Alongside the steel machineries that destroy the environment and biodiversity, the unprecedented amount of information dissemination brought by the Internet is also gradually destroying the diversity of existing languages. Faced with the growing importance of development and communication, speakers of minority languages/dialects are almost unable to withstand this rolling tide: after struggling to learn the popular language and finally gaining the convenience of communication, they will also be burdened with “losing ancestral culture”. Language as a tool for information exchange has indeed allowed more people to integrate into modern society, allowing mankind as a whole to accelerate its development; but at the same time, mankind is gradually losing the significance of language as a cultural carrier, and the disappearance of every niche language is the fall of a bright star in the galaxy of world cultures. Many languages are already forgotten in the long river of history along with its unique vocabulary, expressions, customs of the people who use it, etc.

Specific to China, many languages from different regions gradually disappeared with the promotion of Mandarin in the past dynasties. Nowadays, the promotion of Mandarin is gradually deepening this trend. China’s “Thirteenth Five-Year Plan for the Development of National Language and Writing Enterprises” also clearly points out that improving the Mandarin ability in rural areas is demanding nowadays. But on the other hand, the time consumption and cost of learning a new language is huge, which has also resulted in many post-2000s who grew up in areas with minority languages and Chinese dialects no longer able to speak only Mandarin and not their own local dialects.

So, in this era of Mandarin for mainland Chinese speakers, how should dialects find a place to exist?

Language Usage Hierarchy

In order to describe the evolution and disappearance of language, we might as well build a simple model.

Each person’s native language is usually directly inherited from people close to him, such as his/her family and friends. This also explains why speakers of a certain language/dialect are concentrated in a certain geographic area. And when this person passes the childhood stage and begins to seek more and wider connections, things start to change.

We will introduce the following 3 assumptions in our model:

Assumption 1: Everyone has one and only one native language, and bilingual native speakers are not considered in this model.

Assumption 2: The purpose of all people using language is to facilitate communication. Language researchers and enthusiasts are not considered in this model.

Hypothesis 3: Learning a new language requires a lot of time and energy, so the decision to learn a new language must be based on the fact that the benefits it can bring us outweigh the investment.

We can calculate an “influence” for each language/dialect. Whether you measure the influence of a language/dialect by the number of native speakers, the number of speakers, frequency of use, or whichever metric you define, one thing is certain: the influence of different languages varies greatly. Small. The influence of some languages can be so small that you can’t understand others’ language outside your own village; the influence of some languages can be so big that its usage can cover a country (like Mandarin), or it can become the common language of the whole world (like English).

Based on these assumptions, if you are a young person just leaving your village and started to learn a second foreign language, which language would you choose to learn?

In real life, the answers to this question varies from person to person since many different factors influence one’s choice of a second language. But here, we simplify our model to only include two influencing factors: the degree of similarity between the foreign language and the native language, and the influence of the foreign language.

- The more similar a foreign language is to someone’s native language, the less time and effort one can spend learning the language.

- The greater the influence of a foreign language, the more people someone will be able to communicate with after learning the foreign language, which will bring greater benefit to themselves.

If only these two factors are considered, and based on the Hypothesis 3 mentioned previously, a reasonable conjecture is: If a language A is not as good as another language B in terms of learning difficulty or influence power, then A is not worth learning as a foreign language.

For example, suppose that you were born in a Min dialect island within Hangzhou. Your native tongue is Min dialect, but most people around you speak Hangzhou dialect or Mandarin, with few cases might use Min dialect, and even fewer cases might use Cantonese. Then if we plot the influence and similarity to Min dialect on a graph, we will get:

Then, with the previous conjecture, since the influence of Cantonese and Shanghainese in your environment is less than the influence of Hangzhou dialect, also, these two languages is ‘linguistically’ farther away from Min dialect, then both language does not worth learning comparing to Hangzhou dialect. In this table, only 2 languages are worth of learning: Hangzhou dialect and Mandarin.

This example may not feel familiar to western readers. An analogy of a similar case might be someone coming from a small Serbian community in west Poland, where the main languages spoken there are (1) Serbian (3) Polish (2) German (4) English. Assume his/her native language is Serbian.

Since German is both “farther away” from Serbian in words and grammar and used less common in his/her daily life, he/she would less likely choose to learn German as his/her second language.

Language Evolution and Disappearance

Based on our previous assumptions and the derived language hierarchy model, we can try to analyze the dynamic changes of language.

First we need to introduce another assumption:

Hypothesis 4: As time goes by and one’s language ability declines, one might forget the learned languages to varying degrees. The languages one uses most often are usually the least likely to be forgotten.

Specifically, forgetting may take the following different forms:

- Phonological: forgetting the pronunciation unique to the first language, and having a different accent when speaking the first language.

- Morphological: forgetting the words and word formation of the mfirst language, and replacing them with corresponding words in the second and third languages.

- Syntactic: forgetting the grammatical rules of the first language, and replacing them with the rules of the second language.

If you have learned a second language for a long time, you probably have experienced one or more of these. For example, when I was exposed to English for a long time, I could not help but think of English words and the word structures in English when speaking Chinese (such as using “xxx化” more often, which corresponds to “xxx-ize” in English).

According to hypothesis 4, it seems that languages with less influence will inevitably merge with languages with greater influence. This seems pessimistic, but in reality, many languages with less influence have indeed been replaced or assimilated by languages with greater influence. For example, under the influence of English, many Native American languages have been endangered or disappeared in the last century even without any policy enforcing English as the single language. In large cities in China, many former dialects are gradually shifting closer to Mandarin in pronunciation, such as the comparison of the new and old pronunciations of Chengdu introduced by Bilibili uploader 小白的二次元.

Of course, it should be noted that these assumptions are not completely consistent with reality. For example, we didn’t consider the inter-generational transmission of language. When a child learns a language from the elders, the pronunciation, words, grammatical rules, etc. that he/she learns may be slightly different from the words and grammar that the elders uses. Such differences may not be obvious within one generation, but as time accumulates, even the same language will gradually evolve and differentiate. It’s similar to how organisms reproduce, evolve, and differentiate. I also found some papers that use mathematical modeling methods to study language evolution, which can be seen here: [2].

2024.05.31 comment

I also need to admit that this model cannot fully explain every individual’s choice for learning other languages. It is entirely possible for one to learn a language that is very different from his/her native language and has little impact on his/her life. Also, since this model is not strongly based on real-world cases but more of a subjective speculation, so it may differ greatly from actual situations.

Case Study: Longquanyi district, Chengdu, Sichuan

During the last winter vacation, I went to Chengdu specifically to learn about the customs and culture around Chengdu.

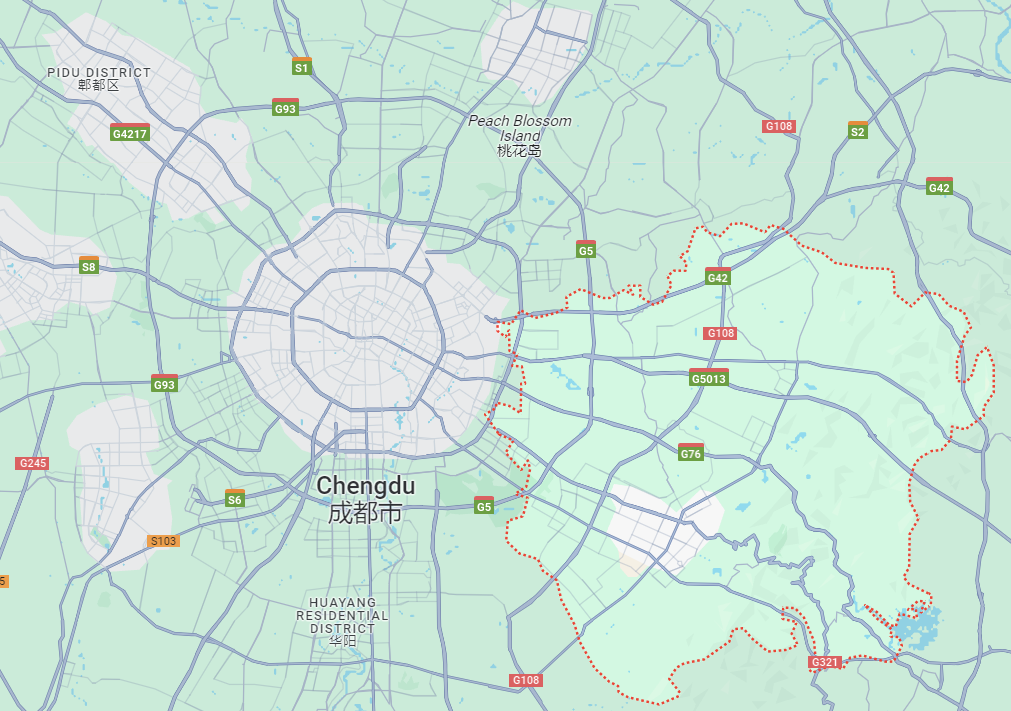

Although Longquanyi is only 30 kilometers away from the city center of Chengdu, the dialects in two places have many differences. Chengdu city and most rural areas around it speaks Chengdu dialect, which belongs to the Southwestern Mandarin branch of Mandarin. However, in Longquanyi, the most spoken dialect is the Sichuan Hakka dialect under the Hakka dialect, since most residents are Hakka people who came to Chengdu during 湖广填四川 (the Great Migration from Hubei, Hunan, and Guangdong to Sichuan). In The Data Collection, Recording, and Display Platform for the Chinese Language Resources Protection Project, there is detailed introduction of the language. Chinese Wikipedia also have corresponding articles, so I won’t introduce the language in too much detail.

Location of Longquanyi

Location of Longquanyi

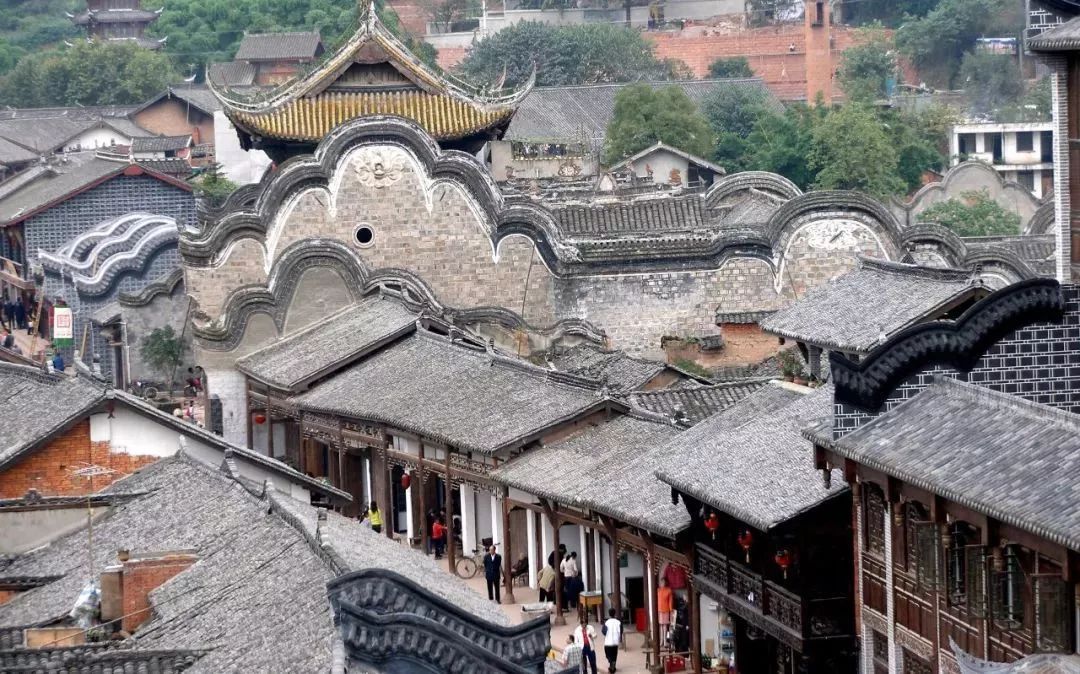

湖广会馆 (hú guǎng huì guǎn, Hu-Guang Meeting House):After the immigration, the meeting house is built as a social and meeting place for people from Hu-Guang area.

湖广会馆 (hú guǎng huì guǎn, Hu-Guang Meeting House):After the immigration, the meeting house is built as a social and meeting place for people from Hu-Guang area.

Longquanyi District is a Hakka dialect island in Sichuan. Due to the growing need for communication, most Longquanyi locals now speak two dialects - Hakka and Chengdu dialect, with increasing number of people who can speak Mandarin fluently. In the most famous scenic spot in Longquanyi - Luodai Ancient Town, almost all staff there can speak Mandarin, Chengdu dialect, and Hakka dialect due to inflow of tourists from all over the country. Therefore, it can be seen that near the tourist attractions, the three dialects are ranked in this order of influence: Mandarin > Chengdu dialect > Sichuan Hakka.

洛带古镇 (luò dài gǔ zhèn, Luodai ancient town)

洛带古镇 (luò dài gǔ zhèn, Luodai ancient town)

Ever since the Hakka people moved to Longquanyi, their Hakka language has never stopped evolving. I interviewed some locals near tourist attractions and asked them how certain words are pronounced in their local dialects. I recorded the conversations with the interviewees’ consent. The results are shown in the following table, compared with the pronunciation of Meixian Hakka dialect (the dialect in east Guangdong, usually set as the standard of Hakka dialect) given on Wiktionary:

| character | Meixian dialect, Guangdong (IPA) | Longquanyi dialect, Chengdu (IPA) | Chengdu dialect, Chengdu (IPA) | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 一 | /jit̚/ | /ji/或/jao/ | /ji/ | one |

| 二 | /ŋi/ | /ni/ | /ɚ/ | two |

| 三 | /sam/ | /san/ | /san/ | three |

| 四 | /ɕɨ/ | /ɕɨ/ | /sɨ/ | four |

| 五 | /n/ | /oŋ/ | /vu/ | five |

| 六 | /liuk/ | /liu/ | /liu/ | six |

| 七 | /t͡ɕʰi/ | /t͡ɕʰi/ | /t͡ɕʰi/ | seven |

| 八 | /bat̚/ | /ba/ | /ba/ | eight |

| 九 | /giu/ | /t͡ɕiu/ | /t͡ɕiu/ | nine |

| 十 | /səp̚/ | /sɚ/ | /sɨ/ | ten |

| 我(𠊎) | /ŋai/ | /ŋai/ | /ŋo/ | I/me |

| 你(伲) | /ni/ | /ni/ | /i/或/ni/ | you |

| 吃(食) | /səp̚/ | /səp̚/ | /t͡sʰɨ/ | eat |

| 车 | /t͡sʰa/ | /t͡sʰa/ | /t͡sʰe/ | car |

We can see that the pronunciation in Longquanyi Hakka dialect keeps certain features from Hakka language, such as the first and second pronouns; meanwhile, its pronunciation is also becoming similar to Southwestern Mandarin, for example, character “一”, “六”, and “八” lost their consonant stop at the end.

How to Protect Endangered Languages/Dialects?

There are many factors that contribute to the different influences of different languages/dialects.

- Some languages, such as Mandarin, gain greater influence through their status of “official language”. Mandarin, as the only standard language taught in Chinese schools, has become the default language of communication for everyone. People from all over the country can understand each other through Mandarin.

- Some other languages gained influence outside their native language area through the spread of literary and artistic works. For example, in China, Cantonese pop songs, movies and other artistic works during the 80s have an larger influence beyond Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau, making Cantonese a popular language in the literary and artistic circles.

- The influence of technology on language also shouldn’t be underestimated. Technology such as radio, television, and the Internet allows the language to influence across regions and spaces, giving languages that are already very influential more advantages: a more influential language is more likely to be used as the designated language for TV broadcasts or the language used by content producers on the Internet.

Before we start thinking about “how”, we need to first clarify: What is the purpose of protecting these languages/dialects?

Why do we Want to Protect Dialects?

There are many different opinions on this issue and scholars have many different motivations for protecting languages. However, one thing is clear: behind every dialect are a group of people’s stories and splendid culture. Protecting dialects is to protect the endangered culture and to remedy the damage to cultural diversity caused by social development.

Some people believe that a language is only “alive” when someone uses it, and hope to see the language become a “living record” of history rather than just evidence of its existence lying in databases; while some people believe that as long as we record enough information about a language (such as text, pinyin, audio and video, etc.), the language is preserved, and they do not want to see the protection of language/dialects hinder the normal development or progress of society. Both ideas have their own reasons, but also their own limitations.

Some people may compare language with species in biology, thinking that language diversity and ecodiversity can to be protected in the same way, but the two concepts have completely different causes and evolutionary methods, and the two types of diversities have different impact on society.

- First, different species can produce offspring, meaning that organisms will only continue to differentiate and compete with each other. One species can only predate or compete with another species to cause the other to extinct. Language is different. In addition to differentiation and competition, languages can also merge and assimilate with each other. According to the previous model, language fusion is also an important factor in language evolution.

- Second, biological diversity will have a negative impact on production and people’s lives, but the reduction of language diversity will make communication between people more convenient and increase the efficiency of our society. The purpose of protecting language is to protect the language and culture itself, so that people in later generations can read and understand today’s language.

Then What to Do?

Nowadays, influences of Mandarin to Chinese dialects are everywhere. Not many ways of protecting dialects are left. Obviously, force isolation of dialect speakers from the outside world is inhumane and contradictory to people’s will and society’s developement. As for what else we can do, it depends on which side of the spectrum you fall on on the previous question.

If you align with the first opinion, then you would want to preserve a language by creating a detailed archive. In the past, when audio and video recordings are not invented, we could only record the text of a language by compiling dictionaries, but now we can also record more comprehensive information such as voice and videos. Today, language institutions around the world have established many such archives. For example, you can see the dialects of each city and each region in China in detail on the Chinese Language Resource Protection Project Recording and Display Platform. As long achives of a language is detailed enough, people in later generations can relearn the language based on these archives.

If you align with the second opinion, then you probably agree with this statement: The best way to protect a language is to increase its influence. From signs and slogans to literature, art, and music works, only when more people understand, recognize, and appreciate a language can it gain more opportunities for dissemination and greater influence. However, this method is difficult to implement under the current language policy in China which strongly prompts Mandarin. Even Cantonese, a language that became popular throughout the country 30 years ago with Hong Kong movies and Hong Kong pop songs, is now declining in usage.

But no matter what we do, language will evolve naturally. The archives of each language can only reflect the pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar and other information of the language in a certain period of time. The language used by people will also undergo constant changes in sounds and words: the addition of new words, the removal of old words, etc. Therefore, whether it is to establish archives or increase influence, it is impossible to accurately preserve a language permanently.

In short, language protection is a long and arduous task, and it contradicts with social and economic development in many cases. Progress or tradition, this is an issue to be constantly discussed.

Reference

[1] de Swaan, Abram. ‘Endangered Languages, Sociolinguistics, and Linguistic Sentimentalism’. European Review, vol. 12, no. 4, 2004, pp. 567–580, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798704000481.

[2] Stauffer, Dietrich, and Christian Schulze. ‘Microscopic and Macroscopic Simulation of Competition between Languages’. Physics of Life Reviews, vol. 2, 03 2005, pp. 89–116, https://doi.org10.1016/j.plrev.2005.03.001.

[3] 黄艺华. 基于方言之间的预测相似度进行方言聚类, zhihu, 26 Mar. 2022, https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/464735745.